As the calendar year draws to a close, communicators are tasked with shaping or contributing to the organisation’s master communication plan for the year ahead. This process is not just about outlining activities or filling a budget spreadsheet. Done well, it is about setting the agenda, aligning stakeholders, and ensuring that resources are committed to programmes that can deliver genuine value.

Too often, communicators fall into the trap of approaching this process from a purely tactical perspective. They itemise campaigns, list activities, and attach cost estimates without anchoring their requests in broader organisational goals. This leaves their plans vulnerable to being negotiated down or reframed by stakeholders in ways that reduce their strategic impact.

The challenge, therefore, is to rise above short-term, activity-driven planning and manage conversations about resources at the level of goals, outcomes, and value.

The Pitfall of Activity-Driven Planning

When communicators think in terms of objectives framed narrowly as outputs — press releases, campaigns, or events — resource forecasts are tied to a tally of tasks. This invites stakeholders to push back in two unhelpful ways.

First, they may negotiate for more work to be completed with fewer resources. Second, they may treat the communicator transactionally, asking for unit costs of each activity as though buying commodities.

Neither approach helps communicators demonstrate their strategic role. By tethering budgets to outputs instead of outcomes, communicators create a frame where their work is measured only in terms of visible activity, rather than contribution to organisational priorities. Stakeholders then hold more power in resource discussions, because they can demand efficiency gains without regard for effectiveness.

The result is a cycle in which communicators defend activities rather than shaping strategy. Over time, this reduces credibility and trust, as it positions the communicator closer to a project coordinator than a planner or strategist.

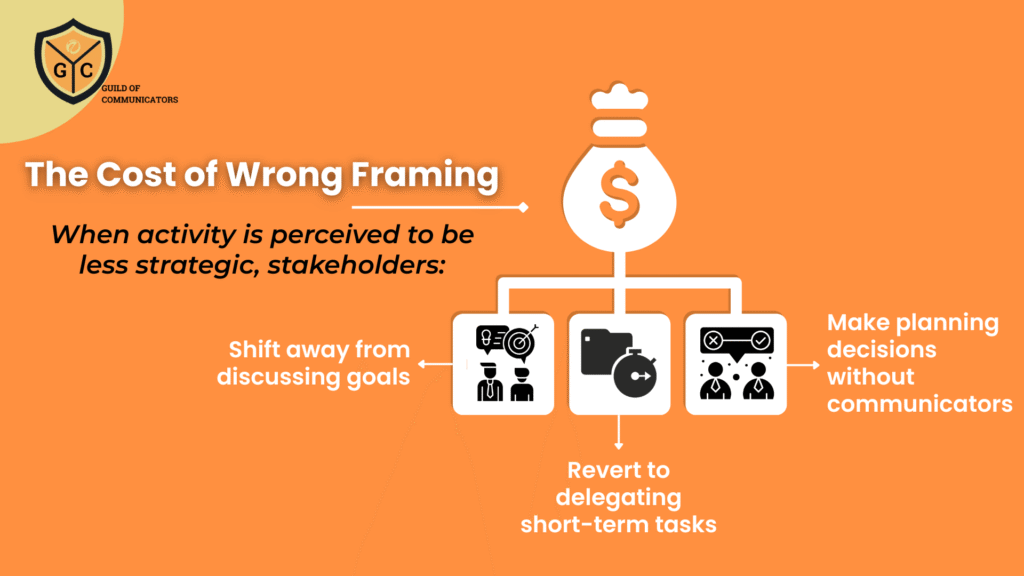

The Cost of the Wrong Framing

The implications of activity-driven planning are significant. Once stakeholders perceive communication as operational rather than strategic, they shift the discussion away from organisational goals and towards short-term tasks.

This shift strips communicators of influence, as future outcomes are often dependent on markets, customers, or stakeholder responses — factors beyond anyone’s direct control.

When communicators are asked to guarantee results they cannot fully control, dissatisfaction is almost inevitable. Stakeholders may question the value of the plan if outputs do not directly translate into outcomes, and trust in the communicator declines. The individual is then forced to reactively justify work after the fact, rather than proactively shaping the conversation.

This erosion of trust has lasting effects. Once a communicator is seen as less strategic, it becomes harder to regain a seat at the table where higher-level planning decisions are made. To avoid this outcome, communicators must ensure that the way they frame their plans positions them alongside senior leaders as strategic partners.

Think About Your Foundations

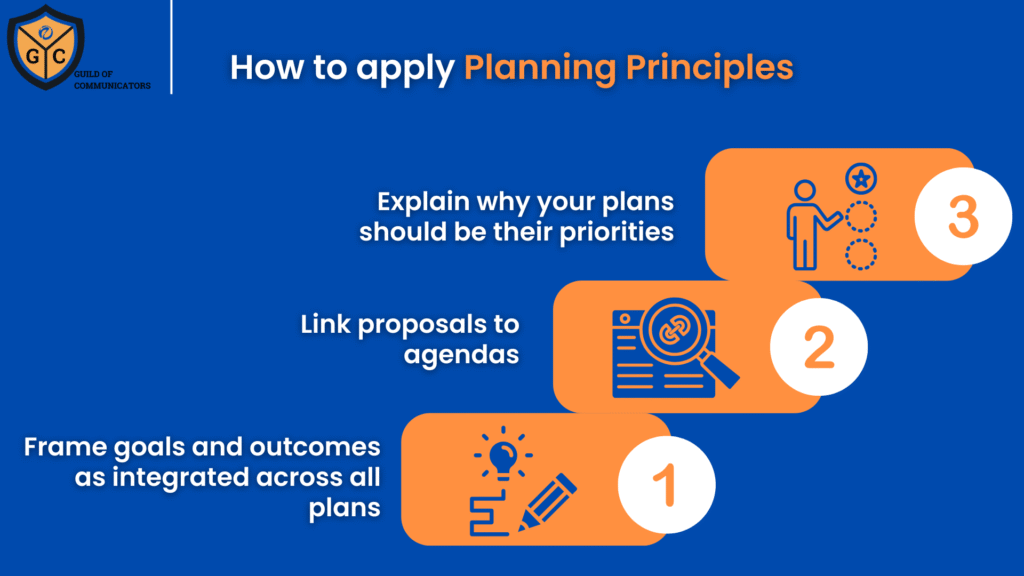

Securing approval for a master communication plan in 2026 requires more than listing activities and requesting budgets. It demands a shift in how communicators frame their work and their role.

Here are two key principles to adhere to when putting together the master communication plan:

Negotiate at the Goal–Outcome Level: Plans must be built around outcomes that matter to the organisation, not just outputs. This principle requires communicators to tie budget requests to how communication supports strategic goals — reputation, engagement, or stakeholder alignment — rather than to the volume of work to be delivered. Doing so shifts the negotiation from “how much activity for this budget” to “what value the organisation will gain.”

Anchor Discussions in Collaboration and Value: Budget planning should not be presented as a one-sided request. It must demonstrate how communication outcomes create value across the organisation, while also showing willingness to collaborate. By framing resource allocation as an investment in shared priorities, communicators can counter the perception that communication is a cost centre.

Psychology and Stakeholder Perception

Beyond the structural principles, communicators must understand how stakeholder perceptions are shaped by psychology. Stakeholders are not neutral evaluators. They carry cognitive tendencies that influence how they view plans and the people presenting them.

Authority bias can cause stakeholders to assume that only senior leaders operate at the strategic level, while communicators are “doers” rather than thinkers. Framing effects mean that if a plan is presented in terms of activities and costs, stakeholders will evaluate it transactionally. Status quo bias leads decision-makers to favour current allocations of resources, resisting shifts unless a compelling case is made.

Recognising these tendencies is essential. Communicators must present themselves and their plans in ways that counteract bias. This means framing discussions around goals and outcomes, explicitly demonstrating strategic alignment, and providing evidence that justifies a reallocation of resources. The communicator’s role is not only to design the plan, but to design how it will be perceived.

Applying the Principles for Planning

For communicators, mastering these principles represents an opportunity. It is a chance to step beyond the role of activity manager and become a trusted strategist.

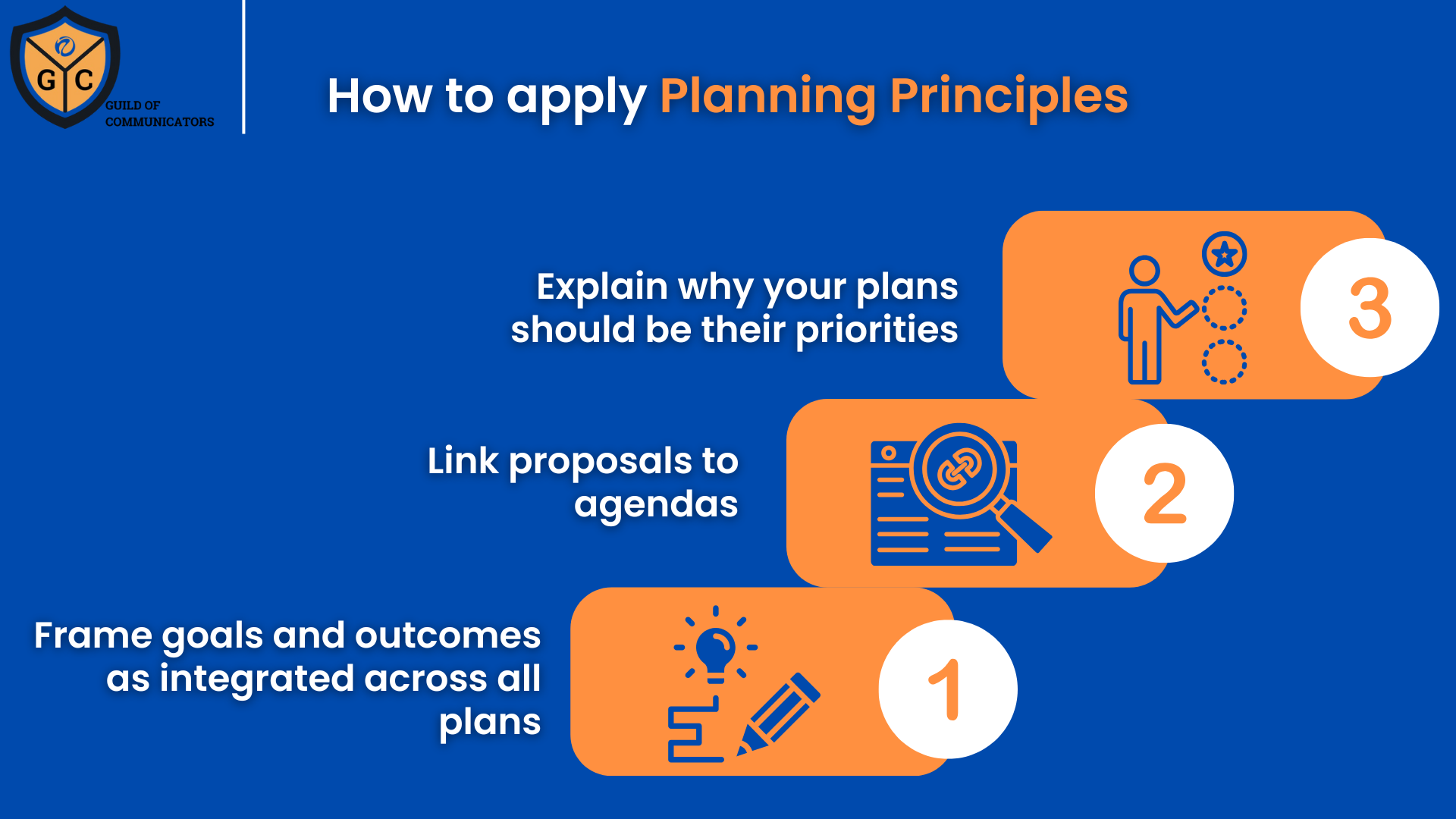

Here are three more principles to incorporate into your process:

Connect the Dots at the Master Plan Level: Stakeholders may expect to hear about campaigns and activities, but communicators must link these to the larger master plan. Rather than presenting a fragmented list of initiatives, the communicator should demonstrate how each campaign connects to overarching objectives. This reinforces the perception of coherence, alignment, and strategic intent.

Treat Resources as Priorities: Budgets are not simply about covering costs. They represent prioritisation decisions. Communicators should frame requests by showing why resources should shift to their programmes compared with other demands. This means articulating the potential value derived from communication, and why it deserves precedence.

Build Relationships Through Win–Win Outcomes: Resource negotiations are not zero-sum. Communicators should design plans that integrate stakeholder agendas, creating opportunities for joint wins. By expanding proposals to include mutual benefits, communicators strengthen alliances and build the trust necessary for future negotiations.

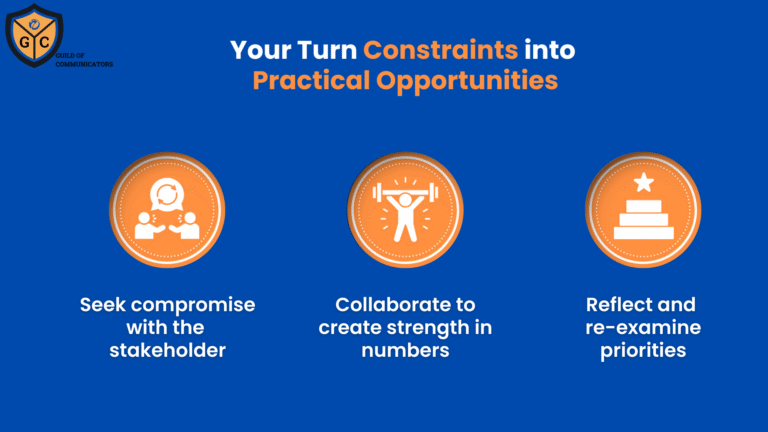

To move from theory to practice, communicators should keep three applications in mind.

- Integrate goal–outcome framing into all planning documents. Budgets should show not only the activities and costs but also the outcomes those activities support. This demonstrates value while creating a language senior stakeholders recognise.

- Use resource discussions as opportunities to connect. Invite stakeholders into the planning process by linking your proposals to their agendas. Collaboration at the planning stage builds buy-in before negotiations begin.

- Prepare to explain why resources should shift to communication programmes compared with other options. This requires a clear articulation of value, supported by evidence, and framed in terms of priorities that matter to leadership. Doing so strengthens credibility and reinforces the communicator’s strategic role.

By negotiating at the level of outcomes, collaborating on value, connecting the dots at the master plan level, treating resources as priorities, and building win–win relationships, communicators can position themselves as strategic partners rather than operational executors.

At the same time, awareness of stakeholder psychology ensures that plans are not just well designed but well received. Overcoming authority bias, framing effects, and status quo bias requires communicators to present themselves as peers in strategy, capable of shaping not only communication outcomes but also the organisation’s trajectory. In doing so, communicators can not only secure 2026 plans but also strengthen their standing for years ahead.

*****

Ready to elevate your communications career? The Guild of Communicators is your essential hub for professional growth, offering a vibrant community and best-in-class resources.

- Connect Membership: Ideal for early-career communicators seeking a supportive peer network, over 300 foundational and intermediate courses, and monthly interactive group sessions.

- Elevate Membership: For ambitious professionals, this tier includes premium frameworks, immersive live online workshops, dedicated career coaching, and mentorship with senior industry leaders.

Discover your path to impact and accelerated career growth.

Join the Guild of Communicators today at www.gocommunicators.com.

(For students: If you’re a student, undergraduate or postgraduate, explore our special student referral programme to lock in your membership fee for the second year! Drop us an email to find out more)

——-

Subscribe to join over 1500+ communicators and brands getting value every Tuesday while reading A Communicator’s Perspective, our weekly newsletter.